Diaphragm

Last updated:

28/06/2024Della Barnes, an MS Anatomy graduate, blends medical research with accessible writing, simplifying complex anatomy for a better understanding and appreciation of human anatomy.

What is the Diaphragm

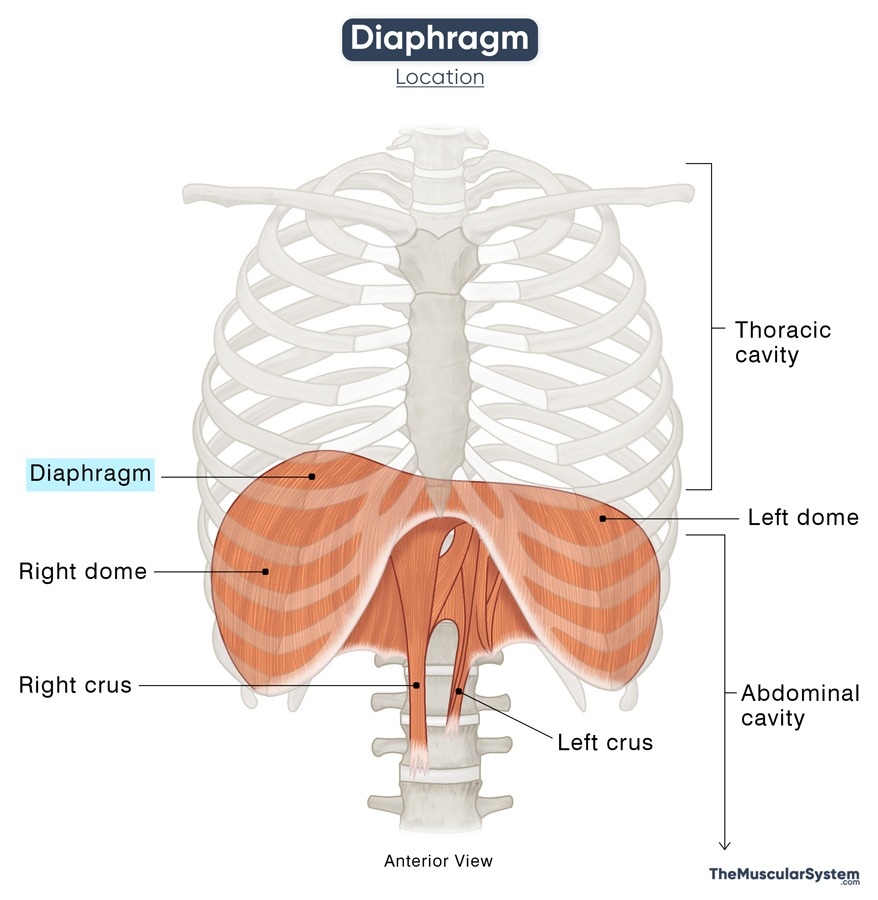

The diaphragm is a large, flat, double-domed sheet of muscle located in the thoracic region of the torso or body trunk. It separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities and serves as the primary muscles of respiration.

Anatomy

Structurally, the diaphragm is divided into its muscular peripheral regions and the central aponeurotic part.

Location and Attachments

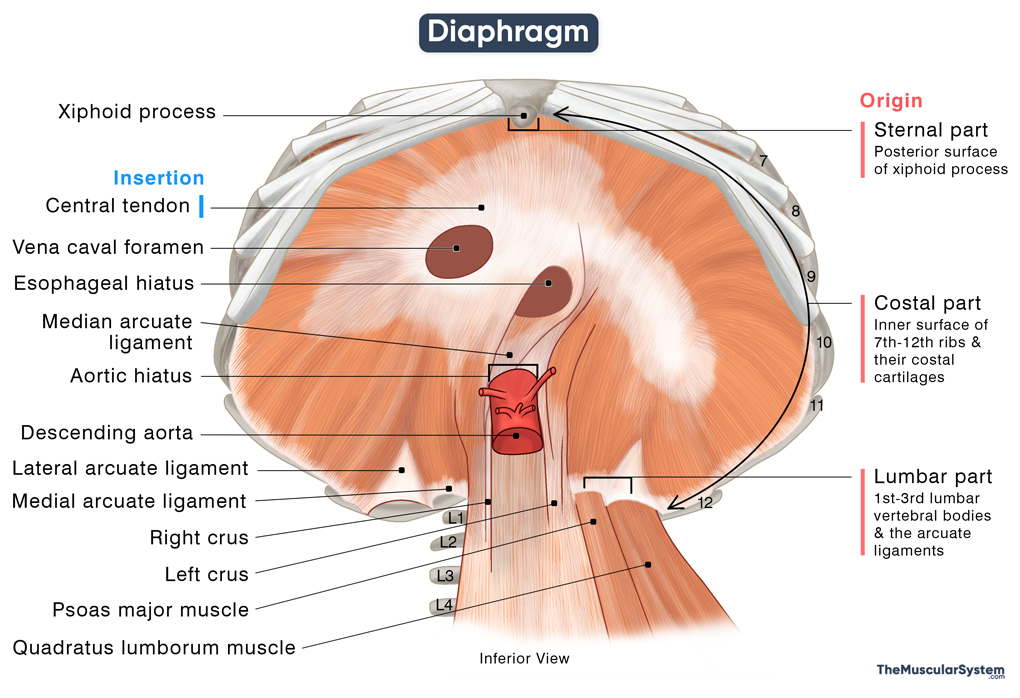

The peripheral muscular portion originates in three parts, from three different points.

| Origin | Sternal part: The back side of the xiphoid process. Costal part: Inner surfaces of the 7th to 12th ribs and their corresponding costal cartilages Lumbar part: 1st to 3rd lumbar vertebral bodies and the arcuate ligaments |

| Insertion | The central tendon of the diaphragm |

Origin

Being a musculotendinous sheet, the diaphragm’s muscle fibers arise from the sides, coming together at the center. Thus, it has multiple peripheral attachments and a single central attachment. As mentioned above, the peripheral attachments originate from three different points:

- Sternal part

It arises as two fleshy muscular strips from the posterior side of the xiphoid process, the small triangular bone at the distal end of the sternum.

- Costal part

It originates from the inner surfaces of the costal cartilages and adjacent bony portions of the 7th to 12th ribs. This includes the costal cartilages of ribs 7 through 10 and direct attachment to ribs 11 and 12 (the floating ribs).

- Lumbar part

As the name implies, the lumbar part of the diaphragm attaches to the vertebral column. The medial and lateral arcuate ligaments serve as two major points of origin for this part. The medial arcuate ligament attaches to the body of the 1st lumbar vertebra, while the lateral arcuate ligament attaches to both the 1st lumbar vertebra and the 12th rib.

Additionally, two tendinous structures arise directly from the lumbar vertebrae.

- The longer and larger of the two, the right crus originates from the anterolateral side of the 1st to 3rd lumbar vertebral bodies and their intervertebral discs.

- The comparatively shorter left crus originates only from the 1st and 2nd lumbar vertebrae and their intervertebral discs.

The two crura join together approximately at the T12 vertebral level to form the median arcuate ligament.

Some muscle fibers from the right crus wrap around the opening where the esophagus meets the stomach. They act like a gate, preventing stomach contents from flowing back up into the esophagus.

Insertion

The muscle fibers from all three parts radiate and course towards the center, where they converge and form a single aponeurosis called the central tendon. It has a unique trifoliate shape, with the triangular anterior leaf pointing toward the xiphoid process while the left and right leaves extend sideways and backward.

The central tendon ascends to attach to the lower side of the fibrous layer of the pericardium.

Relations With Surrounding Muscles and Structures

Being a domed sheet-like muscle, the diaphragm has two surfaces — the upper or thoracic surface that forms the floor of the thoracic cavity, and the lower or abdominal surface that encloses the superior side of abdominal cavity to form its dome-shaped roof.

As the central tendon extends upward to connect to the pericardium, the diaphragm creates two domes on either side of this connection. In a resting position, the right dome sits a bit higher than the left, likely due to the liver lying just beneath it.

Apart from the pericardium, the thoracic surface is also in contact with the pleura of the lungs. On the other side, the liver, spleen, and stomach lie in direct contact with the abdominal surface.

The psoas major muscle lies behind the diaphragm, traversing through the medial arcuate ligament, which forms a portion of the diaphragm’s posterior boundary. Lateral to the psoas major and also posterior to the diaphragm is the quadratus lumborum, covered superiorly by the lateral arcuate ligament.

Since it forms the barrier between the thoracic and abdominal cavities, the diaphragm has multiple openings that allow passage to several vital structures.

Apertures (Openings) in the Diaphragm

There are 3 major and 5 minor openings or pathways.

The major pathways are:

| Name | Location | Structures that pass through the aperture |

|---|---|---|

| Vena caval foramen (Caval opening) | It runs through the central tendon, where the diaphragm’s right and middle leaflets meet, at the level of the T8 vertebra | i) Inferior vena cava ii) Right phrenic nerve (terminal branches) |

| Esophageal hiatus | Perforates the right crus at the level of the T10 vertebra | i) Esophagus ii) Anterior and posterior vagal trunks iii) Esophageal branches of the left gastric artery and vein |

| Aortic hiatus | It runs posterior to the diaphragm rather than through it, between the two crura and the 1st lumbar vertebra, at the level of the T12 vertebra | i) The descending aorta ii) Azygos vein iii) Hemiazygos veiniv) Thoracic duct |

The much smaller, minor openings are:

- 2 lesser apertures of the right crus allow passage to the lesser and greater branches of the thoracic splanchnic nerves

- 3 lesser apertures of the left crus through which the lesser and greater left splanchnic nerves and the hemiazygos vein pass

- The small aperture running towards the back, underneath the medial arcuate ligament, allows passage to the sympathetic trunks

- The Foramen of Morgagni, between the diaphragm’s costal and sternal parts, transmits the superior epigastric artery (a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery) and the lymphatic vessels of the abdominal wall

- Areolar tissues between the medial and lateral lumbocostal arches separate the pleura and the kidneys’ posterior surfaces.

Function

| Action | Playing a major role in respiration by helping with expanding and contracting the thoracic cavity |

Role in Respiration

Inspiration (Inhalation)

When the phrenic nerves send a signal, the muscle fibers in the diaphragm contract, pulling the whole structure down toward the abdomen. When contracted, the diaphragm becomes flat, expanding the volume of the thoracic cavity, which creates a vacuum (negative pressure). As a result, air rushes into the lungs, causing inhalation.

While the external intercostal muscles play a vital role by elevating the rib cage during inhalation, the diaphragm provides about 75% of the muscle force driving this process.

Sometimes, for variable reasons, the diaphragm may contract involuntarily. Inhaling air at such a time causes the glottis (the space at the back of the throat between the two vocal cords) to close abruptly, leading to a clicking noise that we know as ‘hiccups.’

Expiration (Exhalation)

While the diaphragm is actively involved in inhalation, its involvement in exhalation is passive. After each contraction, it relaxes and returns to its original position and shape. This movement puts pressure on the lungs, making them shrink back so the air is forced out, causing exhalation.

Role in Abdominal Straining

The diaphragm is a barrier between the thoracic and abdominal cavities, preventing abdominal organs from protruding into the chest cavity. It plays a vital role in maintaining intra-abdominal pressure by contracting along with the anterolateral abdominal muscles. This pressure increase is essential for normal bodily functions such as vomiting, urination, defecation, and childbirth.

Role as a Weightlifting Muscle (Valsalva Maneuver)

When weightlifting, the diaphragm helps stabilize the core and spine. This is done through a technique called the Valsalva maneuver. It involves taking a deep breath and holding it while tensing the abdominal muscles. This action increases pressure inside the abdomen, which helps keep the spine stable.

Role in Fluid Circulation

The diaphragm plays a crucial role in fluid circulation within the body. When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts, putting pressure on the inferior vena cava. It helps push blood upward into the heart’s right atrium, where it is pumped to the lungs to pick up oxygen.

Simultaneously, the increased pressure in the abdominal cavity caused by the diaphragm’s movement encourages lymph fluids to flow from the belly into the chest cavity. This movement allows the fluids to gather immune cells and waste products more efficiently, contributing to overall bodily health.

Antagonists

The internal and innermost intercostals depress the rib cage to compress the thoracic cavity during exhalation. On the other side, the internal abdominal oblique muscle contracts and makes the abdominal organs push on the diaphragm to send it back to its original position, leading to exhalation. So, the internal and innermost intercostals and the internal oblique are considered antagonistic to the diaphragm.

Innervation

| Nerve | Phrenic nerves C3 to C5 and the lower 6 intercostal nerves |

Its motor innervation comes from both left and right phrenic nerves that originate from the C3 to C5 spinal nerves. The phrenic nerves pierce through the diaphragm to innervate it on its abdominal side.

Sensory innervation of the central tendon region comes from the phrenic nerves, while the peripheral muscular areas are supplied by the 6th through 11th intercostal nerves.

Blood Supply

| Artery | Superior phrenic arteries, inferior phrenic arteries, musculophrenic artery, and the 7th to 11th intercostal arteries |

Being a large muscle with a complex structure, the diaphragm receives blood supply from multiple directions.

The primary vasculature comes from the inferior phrenic arteries. The left inferior phrenic artery travels upwards toward the left crus and passes from behind the esophagus along the esophageal hiatus. The right inferior phrenic artery runs posterior to the inferior vena cava along the front of the vena caval foramen.

Both the inferior phrenic arteries give off medial branches that connect with each other and with the pericardiophrenic and musculophrenic arteries. At the same time, their lateral branches join together with the musculophrenic arteries and the lower posterior intercostal arteries near the chest wall.

The costal part of the muscle is supplied by the 5 lowest intercostal arteries and the subcostal arteries.

The upper surface of the diaphragm receives blood supply from the superior phrenic arteries.

The left suprarenal vein and the azygos system handle the venous drainage.

References

- Anatomy of the Diaphragm: Osmosis.org

- Anatomy, Thorax, Diaphragm: NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov

- Diaphragm: Anatomy, Function, Diagram, Conditions, and Symptoms: HealthLine.com

- Diaphragm: IMAIOS.com

- Diaphragm: KenHub.com

- The Diaphragm: TeachMeAnatomy.info

- Diaphragm: Elsevier.com

- Diaphragm: Anatomy: Lecturio.com

- The Diaphragm: InnerBody.com

- The Diaphragm: ScienceDirect.com

Della Barnes, an MS Anatomy graduate, blends medical research with accessible writing, simplifying complex anatomy for a better understanding and appreciation of human anatomy.

- Latest Posts by Della Barnes, MS Anatomy

-

Occipitofrontalis

- -

Frontalis

- -

Occipitalis

- All Posts