Achilles Tendon

Last updated:

15/09/2025Della Barnes, an MS Anatomy graduate, blends medical research with accessible writing, simplifying complex anatomy for a better understanding and appreciation of human anatomy.

What is the Achilles Tendon

The Achilles tendon is the thickest and strongest tendon in the human body. It connects the calf muscles to the heel bone, calcaneus, which is why it is sometimes referred to as the calcaneal tendon or heel cord. It can be easily felt at the back of the heel, just below the calf.

The name comes from the Greek hero Achilles, famed for his strength but vulnerable at his heel, where he was fatally struck during the Trojan War.

Functionally, the Achilles tendon is essential for plantar flexion of the foot, a movement critical for walking, running, and jumping. However, it is also one of the tendons most prone to injury. Inflammation of the tendon, known as Achilles tendonitis, is a common condition that causes pain and makes standing or walking difficult.

Anatomy

Contributing Muscles

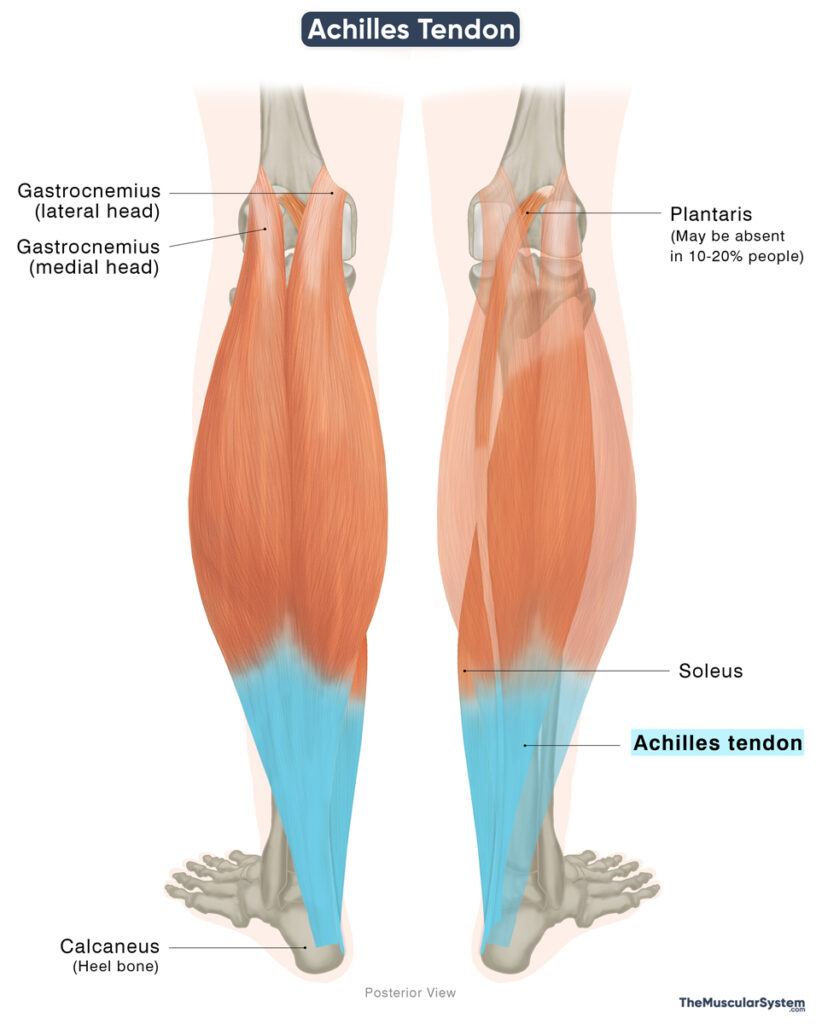

The Achilles tendon is formed by the merging of tendons from two, sometimes three, muscles that together make up the superficial posterior compartment of the lower leg. These muscles originate from different areas around the knee joint and travel down the back of the lower leg.

The muscles involved are:

- Soleus: A large muscle that originates from the proximal end of both the tibia and fibula

- Gastrocnemius: A two-headed muscle, with the lateral and medial heads originating from the lateral and medial condyles on the distal end of the femur, respectively.

- Plantaris (may or may not contribute to this tendon): A long, slender muscle, originating from the supracondylar ridge on the distal end of the femur. This muscle is quite variable and may even be absent in 10-20% of people.

Length and Structure

In adults, the Achilles tendon is usually 11–26 cm long, with the typical length being around 15 cm. It begins as a broad sheet from the aponeurosis of the gastrocnemius, gradually narrowing into a rounded cord as it travels toward the heel. About 4 cm above the ankle, fibers from the soleus join it, and together they insert on the back of the calcaneus.

There are two bursae located at this point to reduce friction and allow the tendon to move smoothly. The subcutaneous calcaneal bursa lies between the tendon and the skin. On the other side, the retrocalcaneal bursa is located between the tendon and the back of the calcaneus.

Fiber Orientation

The fibers don’t run straight down. Instead, they twist as they descend, sometimes spiraling up to 90 degrees. This rotation means the gastrocnemius fibers attach more to the outer side of the heel, while the soleus fibers attach more to the inner side. The plantaris tendon may also blend into the structure, though in some people it remains separate.

Composition

The Achilles tendon can withstand extremely high loads, sometimes up to ten times a person’s body weight. This remarkable strength comes from its two key structural proteins:

Collagen (Type I): The most abundant protein in the body, it makes up most of the tendon’s structure, giving it strength and resistance to stretching.

Elastin: Though present in much smaller amounts, it provides stretch and recoil, allowing the tendon to store and release energy during movement.

Innervation

It is mainly supplied by the sural nerve, which provides sensation to the area. Smaller contributions also come from branches of the tibial nerve.

Blood Supply

The Achilles tendon has a relatively poor blood supply. The posterior tibial artery supplies its proximal and distal parts, while the middle portion is supplied by the fibular (peroneal) artery. All of these arteries are branches of the popliteal artery.

Function

The Achilles tendon plays a crucial role in movement by transmitting the force from the calf muscles to the foot, powering actions like walking, running, jumping, climbing, or descending stairs and standing on your tiptoes.

Its fibers twist before attaching to the heel, a design that improves force transfer and ensures efficient propulsion. This structure allows the tendon to withstand loads several times the body weight — up to ten times during intense activity. Even normal walking places 2-3 times the body weight on it, with running or jumping increasing this load further.

However, the tendon’s strength decreases with age, which helps explain why injuries, including tears, are more common in older adults.

References

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Achilles Tendon: NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov

- Achilles Tendon (Calcaneal Tendon): ClevelandClinic.org

- Achilles Tendon: Kenhub.com

- Achilles Tendon: Radiopaedia.org

Della Barnes, an MS Anatomy graduate, blends medical research with accessible writing, simplifying complex anatomy for a better understanding and appreciation of human anatomy.

- Latest Posts by Della Barnes, MS Anatomy

-

Rectus Capitis Posterior Major

- -

Obliquus Capitis Inferior

- -

Obliquus Capitis Superior

- All Posts